Bevrijd of Niet ? Een indrukwekkend audio verhaal over het bombardement.

Dinteloord werd gebombardeerd de dag voor de bevrijding .

Introduction

On November 4, 2014, it was 70 years ago that Dinteloord was bombed by the Royal Air Force. This dramatic event has played

an important role for a whole generation of Dinteloorders in their later lives

. Details about the exact circumstances could still make the emotions run high for many decades after the event.

Because of the traumatic experiences of the people who experienced the bombing, there was no suitable moment

for a public historical analysis until long after the war .

Only decades after the war did the first testimonies of the bombing become available to interested readers.

After a publication by teacher P. Noom in 1994, where the war and liberation is commemorated in Dinteloord,

a series of publications by local historians with personal testimonies did not appear until 2009 and 2011.

An investigation of archival material with factual information, so far known to the

author of this article, has never been published. However, due to the unexpected availability of an extensive collection of correspondence and archive documents from the hands of a

passionate researcher, the story could be reconstructed within a short time.

The author is therefore very grateful

to the Dinteloord researcher and collector J. Verhagen for making his

life's work. This article was written on the basis of the logs of the Royal Air Force Squadrons involved and the war diary of

the 11th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers as well as correspondence with a British officer who

witnessed the fighting in the polder of the Netherlands up close . The story of the Canadians is based on the literature and records

of the author. The dramatic liberation of Dinteloord

Drs. Ing. RW Catsburg

A liberation without a party

On Sunday 5 November, around 9.45 a column of armored vehicles from the reconnaissance platoon

of the Argylls and Sutherland Highlanders rolled over the bridge over the Vliet in the direction of Dinteloord.

The crawling vehicles carefully followed the winding dike road1, huddling and thumping. The whining of the engine of the steel vehicles

sounded far into the periphery and disturbed the polders that had come to rest. After

Welberg 's terrible shelling in the preceding

days, every day without the thunder of the heavy guns seemed like a day of rest. The Canadians were informed by headquarters that there were British soldiers in the polder

east of Dinteloord. It was about-

The remains of the water tower on the North Sea dike.

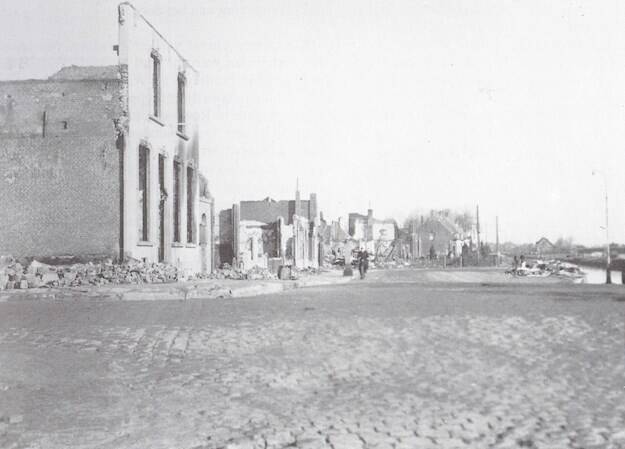

Het gemeente huis kort na het bombardement.

fired at the relevant church towers. First the southernmost tower had to suffer.

The building

of the Reformed Church collapsed with a direct hit . Sixteen rockets hit the target, while an equal number

exploded in the immediate vicinity . Then the reformed

church came into view. Twenty-four rockets hit the target. The pilots saw white smoke appear in a flash and were already aiming at the third and last tower. The ruin of this last church building,

the Catholic Church, was left burning behind after the impact of 24 rockets. The pilots used a total of 96 missiles,

64 of which hit the target. As a final, the Havenweg was shot at with the onboard machine guns, which resulted in a huge explosion

occurred. The pilots reported that an ammunition store had been hit. At 10.55 am they all had landed safely again. The steaming coffee was ready in the

canteen. Prior to the attack of the Typhoons of No. 266 Squadron, were already eleven Spitfires IX

of No. 33 Squadron has been active from 10 am above the village. Like hawks, the aircraft dived

into the undefended village. According to the war diary, they had successfully bombarded and fired troop concentrations

north of Dinteloord

.

The Dutchman Jan Linzel was among the pilots. Linzel wrote about Dinteloord in

his memoir: 'On November 4 we bombed and shot Dinteloord in the morning.

Our troops were stopped on the outskirts of this village'13.

A Belgian squadron, no. 349 (Belgian) Squadron contributed to the destruction of the polder village. From the base in Maldegem,

Flight-Lieutnant Siroux had taken off with eleven colleagues to attack German positions in Klundert. Around 10 am they shot at positions at

Dinteloord. They were able to get results in the short time they were above the village.

Fate is bad for Dinteloord

As if fate had not been enough with the residents of Dinteloord, the following fighter planes were already on their way. No. 302 (Polish) and No. 317 (Polish) Squadron had taken off from the Sint-Denijs air force base with the assignment to attack targets in Rotterdam. For unknown reason had the Spitfire

LF IX aircraft did not reach the targets in the Maas city and were given permission

fen men of the 11th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers, 49th (Polar Bear) Infantry Division, who had entered the Prinslandse polder from Oud-Gastel in the direction of Dinteloord. Last

Saturday night two Canadian soldiers from the Algonquin Regiment were wounded just past the bridge over the Vliet when a Scottish

soldier used his hand grenade. The Canadians had run away when the Scotch asked them for the password.

To avoid a second confrontation, the tense scouts of the Argyll and

Sutherland Highlanders of Canada drove extra carefully on the muddy road. Unscathed, the first carriers unsuspectingly entered

Dinteloord via the Stoofdijk.

The Canadian boys were not brought in the way they were used to. There was

not exactly a festive mood in the village. On the contrary, the welcome was very cool.

An understandable situation given the circumstances.

The village had a dramatic sight.

The center was a plain of rubble and

broken blackened beams. The air was heavy with dust and the smell of fire.

Only a few people were left in the village.

The few residents who showed

up had injuries that were provisionally linked. After the sight of the destroyed

village center and the distant attitude of the population, the bewildered soldiers continued their march in a depressed mood towards

Dintelsas. Saturday, November 4; a day like so many ...

A day prior to the cool entrance of the liberators in Dinteloord, the airmen of the no. 266 (Rhodesia) Squadron at Deurne airport received instructions for a

new combat assignment. For the pilots it was a day like many others. They had been chasing the Germans

for many months and every day they got new targets to shoot high from the air. Often, their Hawker

Typhoons Ib planes flew far beyond German lines to use their missiles to shoot the enemy's supply lines.

That Saturday they were told during the briefing that eight aircraft from A-Flight and four from B-Flight had to support the army with an attack on three observation posts

were located in the church towers of a village. The recognition code for the attack was' XYN4'2.

Observation posts were places that the opponents used as a lookout post to view the approaching

enemy. Church towers or water towers were often used for this. Such a post usually had a radio or telephone connection to the hinterland, so that the enemy's position could be passed on to headquarters or to its own guns. After the battle in West Brabant, due to this tactic, only a few tall buildings were

standing. Just after 10 a.m. on Saturday, November 4, they were all in the air and at 10.25 a.m.

they achieved the goal. The extinct streets of Dinteloord lay in the depths of their crates like a tangle of ribbons. Shortly thereafter, the planes skimmed

over Dinteloord with crackling on- board guns. With graceful dive flights and roaring engines, the rockets were made according to the assignment

De Katholieke kerk na het bombardement.

De watertoren van Dinteloord voor hij was opgeblazen.

De havenweg na het bombardement

secondary purpose of the mission. Twelve aircraft from No. 302 Squadron were

in action above Dinteloord between 8.30 am and 10.45 am. They threw twelve 500-pounder and twenty-four 250-pounder bombs. According to

the pilots, all bombs hit target. No. 317 Squadron fell behind and was active from 11.40 am to 1.15 pm. The six aircraft dropped four 500-pounder and three 250-pounder bombs on it

target. All the bombs fell in the village, while the Germans fired at the planes with anti-aircraft guns, according to the No. 1 war diary. 302 Squadron. For the Dinteloorders on the ground, the routine jobs of the pilots were a hellish inferno. The deafening explosions completely surprised the population and those who were able to do so fled the village blindly. As a result of the destructive explosions of the

bombs, a fire broke out and the damage in the village was insurmountable. More than 45 residents

were killed by this unfortunate attack. The indignation about the air raid was great among the people of Dinteloord. While the residents for the most part the

had fled into the polder, a small number of those who stayed behind tried to extinguish the many hot spots. A snake of people with buckets put out a fire that afternoon at Bakkerij van

Damme in Westvoorstraat. The small group of hard-working people could not prevent the sky above Dinteloord from turning red from the flames that evening. A yellow sparkling spark of rain blew over the village, while the

streets remained empty because of the curfew set by the Germans. Large fires were able to

consume the Catholic parsonage and post office undisturbed . The advance of the Allied army to the Old Prince polder Until that dramatic Saturday morning

, the liberation had run in Dinteloord as for most villages in the region. The Germans were in fact defeated after the liberation of

Bergen op Zoom on 27 October. Their only remaining goal was to delay the Allied advance,

so that as many men as possible

could escape to Dordrecht via Dintelsas. While the German main force crept underneath the dikes to Dintelsas in geese march, a

few

groups lay scattered everywhere in the polder, armed to the teeth. These men sacrificed themselves to guarantee a safe retreat for their comrades. A few less heroic Germans hid

as unobtrusively as possible in the village to surrender to the Canadians at the first opportunity. The residents of Dinteloord patiently watched as the occupier departed and

withdrew to their homes to await the coming events.

A few grenades had exploded in the village on Friday night, but because there were almost no Germans in the streets,

people were convinced that the liberation could come any time. Just after midnight, in the first hours of November 4, the first

Canadians arrived at the Gummarus Church in Steenbergen. Shortly after noon, armored cars from the Algonquin Regiment reached the flax factory. They reported that

the bridge over the Vliet was partially broken, but could be passed by people. The brigade headquarters

heard about this and decided

to take immediate action. In addition to the Algonquins, the machine guns and mortars of the New Brunswick Rangers and the artillery guns were called. The genius was notified to be a Bailey bridge

build over the Vliet. The 'tower' of a factory (probably the chimney of the flax factory)

was used as an observation tower to direct

the fire. The D and C company of the Algonquin Regiment were chosen for the attack. The men were reluctantly transported

from Welberg in the direction of the bridge. The companies gathered out of

sight in front of the factory. Only an hour and a half after they left Welberg, they started

the attack. The artillery erupted and everything went according to the book. The machine guns threw their deadly load over the water and

smoke and high-explosive shells exploded behind the bridge.

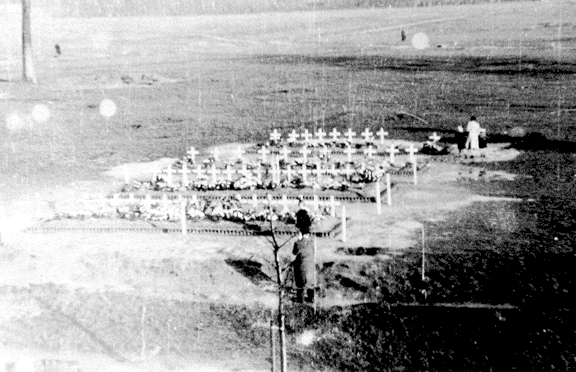

: Plein 13 in Bergen op Zoom acted as a temporary

burial ground for the allied casualties from the region.

Fig. 8: Henry Dupear died in the Beaumont polder. Dupear's

parents placed a small advertisement in the local newspaper

to announce the death of their son. Dupear had two

brothers and one sister. He worked as a milkman before joining the military

. Only months after his death did his

parents receive the official confirmation that he had died.

A officer from the regiment paid a personal visit and

told that Henry

had died immediately through a shot in the head . Further investigation showed that Dupear

was found on the side of a ditch, with his head on his arms,

as if he were sleeping. That's how local residents found him and

buried along the Noordzeedijk. The remains were later

transferred to Bergen op Zoom. Photos collection J. Verhagen

D-company was the first to cross the

bridge and spread into the polder landscape. Fortunately for the infantrymen, the enemy had already disappeared. No. 3 Troop 9th Field Squadron started immediately to build a Bailey Bridge that was reported ready shortly thereafter. While the Canadians

crossed the Vliet from Steenbergen , British units of the 11th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers, 49th (Polar

Bear) Infantry Division had moved west from Oud-Gastel to Dinteloord.

So Dinteloord was eventually approached from two sides; the Canadians via the Bloemendijk and the British via the Noordzeedijk and Zuidlangeweg.

The battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers had a few days of rest in Roosendaal shortly after the fighting in Wouw. They got it

headquarters the assignment to start a rear-guard fight with the last occupiers in the Old Prince's polder. In addition to the entire

battalion, they were assigned one company from the 7th Duke of Wellington Regiment for reinforcement. This company

was deployed in the Beaumont polder, between the Noordzeedijk and the Dintel.

The attack started at 7.30 am on Saturday, November 4. While the infantry watched for the order to start the advance, machine guns and mortars fired

to places where defenders are expected. At 10.30 am the First Way of the Cross had been reached without opposition. Then the Germans opened fire. The conditions in the polder were terrible and the weather only made the stay worse. With some irony, the men called the action in the polder 'Operation Humid', translated

as 'fluid'. Due to the high water level, they could only go to the crown of the dikes and into the open polder. The

scattered German posts could thus see the English approaching from afar and taking them under fire. A platoon, for example, stood in the water for five hours

before they were allowed to retreat. Strangely enough, only one man was taken away sick

due to the circumstances.

With artillery fire, the battalion tried to dislodge the Germans, but the soggy polder ground

smothered the grenades.

Only at 7 p.m. were the B and D companies along an imaginary line between the intersection of the Zuidzeedijk and the Tweede Kruisweg the intersection of the Noordzeedijk and the Eerste

Kruisweg. B-company had removed twenty prisoners of war

from a farm on the Tweede Kruisweg, just before the bridge over the Steenbergse Vliet. At 11 p.m. the previously described incident took place with the patrol of the Algonquin

Regiment, in which corporal Neable and

soldier Turner were injured by the hand grenade of a Scottish soldier.

That evening Sergeant Hill took two sections from the position on the Second Way of the Cross on patrol to the next houses in the distance.

He was probably mistaken on the route, and while the men were crossing a bridge, an explosion occurred. The undermined bridge

is probably the bridge over the Molenkreek. However, this is not easy to trace from the records. A scout was

fatally hit and eight men were injured. Upon returning, it turned out that soldier Cadwick was missing.

The events on Sunday, November 5 That night some German laggards blew in the abandoned and badly damaged Dinteloord

also the water tower, the remains of the bell tower of the catholic church and the mill. A ship was destroyed in the harbor. The mill at the harbor turned out to be too strong in construction,

because despite the large explosion, the brickwork remained intact. Early the next morning, November 5,

the 11th Royal Scots Fusiliers sent a patrol to the same bridge as the night before. There was no trace of the missing soldier.

A platoon searched the buildings near the bridge, but no one was found. Shortly before noon a B company patrol entered the village. To make matters

worse, allied aircraft again appeared that morning above Dinteloord. French no. 341 (F) Squadron reported in her

diary that Captain Girardon left Wevelgem airport at 8.55 am for a mission

northwest of Breda. The target would be indicated with white smoke. Because the captain did not see white smoke above the spot he

identified as the target, he first asked permission to start the attack. When the permission was given, the Spitfires IX attacked. They threw

their bombs and shot their houses at the Havenweg and Molendijk with their on-board guns. With flares, the British

soldiers present were able to warn the planes around 09.30 a.m., after which the aircraft drained quickly. The torture of the now heavily damaged village was not yet ready. The destroyed town

was attacked by the Canadian artillery. Artillery shells exploded in

Catholic church on the Kaai, in preparation for the arrival of the Canadian infantry. Fortunately

, the fire stopped after a short time.

At 10:25 am the Scots made contact with the Canadians who have now arrived on Havenweg. This meeting was the sign for the British to end the action. The

11th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers left for Roosendaal at noon. The battalion left five fatalities in the polder and one missing. The casualties were Corporal Frank Finch and Arthur Heron, soldiers

George Leeming and Fred Guest. The graves of these men are located in Roosendaal. Soldier Cadwick was missing as mentioned earlier. There is no known grave of Cadwick and

his name is not known by the British war graves foundation .

The fate of soldier Cadwick

is unknown, although there were rumors among veterans that he was deserted. Soldier Henry Dupear died in the Beaumont polder. This polder is located on the south bank of the Dintel, close to the sugar factory. His grave was moved to Bergen op Zoom after

he was buried by civilians along the Noordzeedijk. A total of nineteen British soldiers were wounded. Furthermore, on November 4,

the lifeless body of brigade commander MS Erskin, the commander of the 56th Infantry Brigade, was found at the sugar factory in Stampersgat. Wolfgang Linsel and Hans Ruhland died on the Havenweg on November 4 as a result of the

bombardment. Helmut Weiszner lay in a field grave on the Stoofdijk. Viktor Müller and H. Hammerman

lay in a grave along the dike at the

Mariaweg and Eerste Kruisweg. A field grave containing three people was found in the Molendijk. They were victims of an accident.

The trio, H. Strelow, H. Weidlich and

G. Domeier, were part of a team of miners

working with explosives. They had used a fuse that was too short, killing all three of them. Finally, a field grave was found in the Sasdijk with seven

remains. W. Kumfert, G. Schmidt and H. Meyer could be identified,

while four soldiers remained unknown. The German soldier, R. Lichtenreckert, has been missing to date.

The previously described patrol of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada had reached a signed and injured Dinteloord. Yet the soldiers did not dwell for long on the

smoking rubble of the village. Despite their young age, after months of struggle, they were dulled by all misery and destruction. Their

final destination was Dintelsas that they could reach without problems.

Upon arrival at the Dintelsas they found a statue like from 'Dantes' inferno'. Heavily wounded Germans were groaning on their stretchers. Their connection was colored red by the blood.

Despite the rapid response of the Argylls to treat these unfortunate enemies, several died as a result of their injuries.

Highlanders or Canada. Sims served with the battalion in a period after the Battle of the Scheldt. He was wounded in April 1945 by a fragment of a mortar grenade. Dead horses were scattered around the site, as well as various military equipment and all sorts of loot. Large pieces of ham, barrels of butter and large rolls of linen had not been of much use to the thieves.

A white flag was flying above the area torn open with grenade funnels . The

Argylls took around 40 German soldiers prisoners, all of Russian descent. They were already running for the Canadian armored cars from Steenbergen. After the patrol report issued, a column of lorries with soldiers from the Lincoln and Welland Regiment left for Dinteloord. These troops stayed in the village for a few days before finally leaving for the front in Waalwijk.

Finally Dinteloord remained destroyed with a huge war trauma. In the village center, 85 homes were

completely destroyed and 65 buildings badly

damaged. Most of the public buildings in the village were hit. Three churches had collapsed, the distribution office, the public one

school, the water tower, two windmills, hotel Vlamings, hotel De Beurs, café Sweere, café Wijgand, lunchroom Hartman, the post office and the Boerenleenbank were destroyed. Only half of the town hall was still standing. The dry details of the events are relatively easy to reconstruct based on records. The 'why' is harder to figure out. In my opinion it seems strongly that the Canadians or English have concluded

that the three church towers of

Dinteloord were used by the Germans as observation posts. As a result, the

towers had to disappear. The strange thing is that the Germans on Friday, November 3 at 11 p.m. until complete evacuation of all troops from Steenbergen

were transferred. It has been noted from tradition that the remaining German artillery at Mariadijk and Boompjesdijk

fired away the remaining ammunition and chose the hare path. Further shelling of Steenbergen took place

from the Volkerak by German navy ships. According to an eyewitness of the firing

from the water, it was a beautiful firework of bright stripes of colored light trail, which drew the sky with a lot of noise

Only a few remained behind in the polder, which could not delay the Allied advance by more than a few hours. There was no significant German artillery south of the Dintel. It is therefore not strange to assume

that the church towers of Dinteloord

did not serve as an observation post at that time. The assumption that the Germans were using the church towers of Dinteloord was an unnecessary mistake by the liberators.

The conclusion was probably based on a failure to properly assess the intentions of the enemy. It was already known on Friday evening, 3 November, based on information from prisoners of war

the general retreat had begun. A bombing of Dintelsas would have been a more logical action from a tactical point of view. After the destruction of the towers by the kites of No. 266 (Rhodesia) Squadron really went wrong for Dinteloord. While the pilots

of No. 266 Squadron, judging by the war diary, were relatively selective, the two Polish squadrons dropped more than 40 bombs on the village. The bad thing is that Dinteloord was a secondary goal for the Poles

. After all, their primary mission was to eliminate targets in Rotterdam. Maybe there was fog or that the intended locations in

Rotterdam could not otherwise be found. The war diary unfortunately does not provide a definitive answer. The fact remains that the aircraft, due to the same fatal estimation error,

Dinteloord as a secondary goal

. The consequences were disastrous. The liberation of Dinteloord was a necessary

evil. The bombing of the village, on the other hand, is most likely based on a human estimation error and proves the

complete madness of war. It is important to keep trying to permeate our and future generations.

bronnen voorgaande stukken.

1 H.M. Jackson, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada

(Hamilton 1953) 148 -149

2 Library and Archives of Canada, Record Group 24, Vol. 14053,

War Diary Headquarters 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade, October

1944.

3 G.L. Cassidy, Warpath The story of the Algonquin Regiment

(North Bay, 1948) 199 - 200

4 (Glasgow 1963) 311-314

5 Correspondentie Major L. Roswell, 11th Royal Scots Fusiliers,

geen datum.

6 Public Records Office, WO 171/1365, War Diary 11th Royal Scots

Fusiliers, november 1944

7 Correspondentie Deutsche Dienststelle betreffende Duitse gesneuvelden

in Dinteloord, oktober 1986 en November 1993

8 Public Records Office AIR 27/370,, Operation Record Book,

16 www.pipesforfreedom.com

302 (Polish) Squadron Royal Air Force, November 1944.

11 Public Records Office AIR 27/1709, Operation Record Book, no.

317 (Polish) Squadron Royal Air Force, November 1944.

12 Public Records Office AIR 27/1738, Operation Record Book, no.

341 (French) Squadron Royal Air Force, November 1944.

13 Public Records Office AIR 27/1744, Operation Record Book, no.

349 (Belgian) Squadron Royal Air Force, November 1944.

14 P. Gerritse, De Mei-kites (location unknown 1995) 211

15 J. de Visser, Dinteloord during the world war of 1940 to

1945 (part 20), De West -Brabander, no date.